Hall of Fame profiles: Jeff Richgels

June 01, 2011

The day Jeff Richgels asked his mentor if he thought he could hack it out on tour was the day he began to learn what it takes to be great.

“With your ball and my brain, we’d make a lot of money,” said that mentor, USBC Hall of Famer Rich Wonders. “You don’t have a chance!”

Wonders could talk like that by then. He nabbed three eagles in a single USBC Open Championships event in 1982 and earned himself an Amateur Bowler of the Year Award.

Still, those words had to be hard to swallow for a cocky kid from Madison, Wisc. then known as much for his arrogance as for anything he had done on the lanes.

“He used to say things like, ‘After all, I am Jeff Richgels,’” says his girlfriend, Susan Dyhr. “I’m not kidding; it was ridiculous. He has mellowed over the years though.”

The kinder, gentler Richgels that Dyhr knows today may have mellowed since then, but in the meantime he had a lot of work to do if he was going to prove Wonders wrong.

“I’m pretty much someone who doesn’t care what others think,” Richgels says, “but when a bowler like Rich Wonders says something like that, it did impact me. I respected him so much that I wanted to hear from him what I needed to do so that I could do it. It wasn’t like, ‘Well, I’ll show him!’ It was more like, ‘If he says that I need to work harder, then that’s what I need to do.’”

But Richgels already got some idea how much work it would take to be great when he was a ten-year-old bowling alley rat at Village Lanes in Monona, Wisc., where he and his friend and future PBA star Marc McDowell would bowl until their hands bled. And then, of course, they did what any kid who has found the thing he loves would do—they kept bowling.

“There’s no doubt that if they hadn’t turned off the lanes and closed the doors we would have stayed there until our parents came and dragged us home,” Richgels says.

McDowell, a born athlete with the legs of a bull who once kicked a 55-yard field goal, spent more time on the football field during the week than he did in the bowling alley. But by the time the sun rose on Saturday morning, there was only one place in the world where you could find McDowell and Richgels.

“It all really took off when my father took a part time bartending job at Village Lanes,” McDowell explains. “Jeff and I would bowl junior leagues and my dad would be the coach, and then he would take over the bar from ten to six every Saturday. That allowed us to hang around and get unlimited bowling, and then we’d sneak into the bar, throw in a Tombstone Pizza and watch the PBA Tour at 2:30 and go back out and try to be like the pros.”

But just being “like” the pros would never be enough, not for a couple of kids inspired to bowl until their thumbs resembled burger meat after watching their idols clash on ABC. The goal always was to be the pros, and they knew it all along.

“We had this plan that we were going to go try the tour together in the same year in 1986,” Richgels says.

McDowell did not just “try” the tour in ’86—he banked $51, 285 on his way to Rookie of the Year honors.

But the thing about plans is they don’t always hear us when we make them. The plans Richgels had to join McDowell on tour in ’86 were doomed long before he watched his buddy live the dream they had at Village Lanes all those years ago.

Richgels didn’t mind the occasional pickup game of football himself back then. Naturally, he had to play against the biggest kids in the neighborhood—after all, he is Jeff Richgels. And when one of them sent him crashing to the ground in a rough tackle that trapped his right wrist under him and broke it, he took the tough guy route and played more ball later that day as his wrist swelled to the size of a grapefruit.

“Yeah, that was pretty stupid,” Richgels says. “It hurt like crazy.”

Ten days later, Richgels still had not even gone to the doctor. When he finally did, the doctor offered to break his wrist again so that it could heal properly. And that’s when Richgels discovered that the tough guy in him had taken the day off; his answer was a quick “no thanks.” So they put a cast on it and hoped for the best.

It’s easy for Richgels to question the wisdom of that particular decision now that he is several surgeries into a bowling career hampered at times by a wrist that’s about as sturdy as a wishbone. But when you’re ten years old and your father’s best advice is to “rub some dirt on it” and carry on, well, it’s hard to see how things can turn out much differently.

“Bless his heart, my dad grew up in the depression,” Richgels explains. “He was a ‘rub some dirt on it’ type of guy,’ a very stoic guy.”

Stoicism is great if you’re playing tackle for the Packers, but probably not if you bust a wrist while tossing the ball around the yard with kids from the block in suburban Madison. Surely that is a thought Jeff Richgels has pondered ever since, but never more frequently than during the difficult years he spent chasing his dreams around the country on the national tour.

“I lost count of the number of tournaments where I was in the top five or 10 after the first 12 games, and then when I woke up the next day my hand would be so tight that it felt like somebody had lengthened my span about an eighth of an inch,” Richgels recalls. “By the end of 1988 I could hardly throw the ball, and I ended up getting reconstructive surgery in February of 1989.”

But Richgels isn’t about to suggest that a bum wrist kept him from becoming the next Norm Duke.

“I spent two years proving definitively that I do not belong out there with those guys, wrist surgery or no wrist surgery," he said in 2005 to the Capital Times, the newspaper for which he works as a web editor while keeping an active bowling blog called “The 11th Frame.”

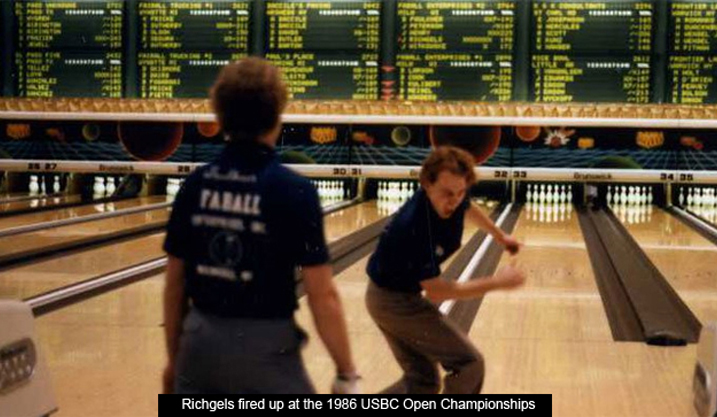

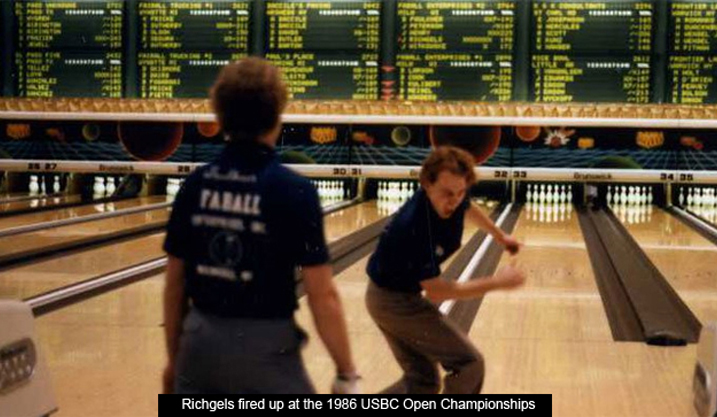

Even so, with 29 PBA regional titles to his credit, four USBC Open Championships eagles, and a 1997 Open Championships performance in which he bowled 90 clean frames, you would think that Richgels looks back and wonders what might have been. But then you wouldn’t know Jeff Richgels.

“I don’t know if I would have had a year like Marc did in 1992, but the more success he had the more confident I became that I would have had at least a handful of titles had my wrist cooperated,” Richgels says of watching McDowell win three titles in 1992 including the Firestone Tournament of Champions. “It satisfied that thing in me that wondered how good I could have been had my wrist not hindered me.”

Another thing that Richgels no longer wonders about is whether his spectacular USBC Open Championships record—capped by a Regular All-Events title in 1997—would allow him to join his mentor in the USBC Hall of Fame someday. That day finally came in November, when USBC announced their election of Richgels in the new USBC Performance category created to ensure inclusion of amateur bowlers that excel in USBC championship events.

“I often say that he proceeded to make a liar out of me,” Wonders says these days of his former protégé and, now, his fellow USBC Hall of Famer. “I have had a lot of people ask a lot of questions and learn a lot of things but never be able to apply them. It takes a lot of desire and intestinal fortitude. Jeff put in a lot of work, and his rewards are well-deserved.”

Reprinted from Bowlers Journal International

“With your ball and my brain, we’d make a lot of money,” said that mentor, USBC Hall of Famer Rich Wonders. “You don’t have a chance!”

Wonders could talk like that by then. He nabbed three eagles in a single USBC Open Championships event in 1982 and earned himself an Amateur Bowler of the Year Award.

Still, those words had to be hard to swallow for a cocky kid from Madison, Wisc. then known as much for his arrogance as for anything he had done on the lanes.

“He used to say things like, ‘After all, I am Jeff Richgels,’” says his girlfriend, Susan Dyhr. “I’m not kidding; it was ridiculous. He has mellowed over the years though.”

The kinder, gentler Richgels that Dyhr knows today may have mellowed since then, but in the meantime he had a lot of work to do if he was going to prove Wonders wrong.

“I’m pretty much someone who doesn’t care what others think,” Richgels says, “but when a bowler like Rich Wonders says something like that, it did impact me. I respected him so much that I wanted to hear from him what I needed to do so that I could do it. It wasn’t like, ‘Well, I’ll show him!’ It was more like, ‘If he says that I need to work harder, then that’s what I need to do.’”

But Richgels already got some idea how much work it would take to be great when he was a ten-year-old bowling alley rat at Village Lanes in Monona, Wisc., where he and his friend and future PBA star Marc McDowell would bowl until their hands bled. And then, of course, they did what any kid who has found the thing he loves would do—they kept bowling.

“There’s no doubt that if they hadn’t turned off the lanes and closed the doors we would have stayed there until our parents came and dragged us home,” Richgels says.

McDowell, a born athlete with the legs of a bull who once kicked a 55-yard field goal, spent more time on the football field during the week than he did in the bowling alley. But by the time the sun rose on Saturday morning, there was only one place in the world where you could find McDowell and Richgels.

“It all really took off when my father took a part time bartending job at Village Lanes,” McDowell explains. “Jeff and I would bowl junior leagues and my dad would be the coach, and then he would take over the bar from ten to six every Saturday. That allowed us to hang around and get unlimited bowling, and then we’d sneak into the bar, throw in a Tombstone Pizza and watch the PBA Tour at 2:30 and go back out and try to be like the pros.”

But just being “like” the pros would never be enough, not for a couple of kids inspired to bowl until their thumbs resembled burger meat after watching their idols clash on ABC. The goal always was to be the pros, and they knew it all along.

“We had this plan that we were going to go try the tour together in the same year in 1986,” Richgels says.

McDowell did not just “try” the tour in ’86—he banked $51, 285 on his way to Rookie of the Year honors.

But the thing about plans is they don’t always hear us when we make them. The plans Richgels had to join McDowell on tour in ’86 were doomed long before he watched his buddy live the dream they had at Village Lanes all those years ago.

Richgels didn’t mind the occasional pickup game of football himself back then. Naturally, he had to play against the biggest kids in the neighborhood—after all, he is Jeff Richgels. And when one of them sent him crashing to the ground in a rough tackle that trapped his right wrist under him and broke it, he took the tough guy route and played more ball later that day as his wrist swelled to the size of a grapefruit.

“Yeah, that was pretty stupid,” Richgels says. “It hurt like crazy.”

Ten days later, Richgels still had not even gone to the doctor. When he finally did, the doctor offered to break his wrist again so that it could heal properly. And that’s when Richgels discovered that the tough guy in him had taken the day off; his answer was a quick “no thanks.” So they put a cast on it and hoped for the best.

It’s easy for Richgels to question the wisdom of that particular decision now that he is several surgeries into a bowling career hampered at times by a wrist that’s about as sturdy as a wishbone. But when you’re ten years old and your father’s best advice is to “rub some dirt on it” and carry on, well, it’s hard to see how things can turn out much differently.

“Bless his heart, my dad grew up in the depression,” Richgels explains. “He was a ‘rub some dirt on it’ type of guy,’ a very stoic guy.”

Stoicism is great if you’re playing tackle for the Packers, but probably not if you bust a wrist while tossing the ball around the yard with kids from the block in suburban Madison. Surely that is a thought Jeff Richgels has pondered ever since, but never more frequently than during the difficult years he spent chasing his dreams around the country on the national tour.

“I lost count of the number of tournaments where I was in the top five or 10 after the first 12 games, and then when I woke up the next day my hand would be so tight that it felt like somebody had lengthened my span about an eighth of an inch,” Richgels recalls. “By the end of 1988 I could hardly throw the ball, and I ended up getting reconstructive surgery in February of 1989.”

But Richgels isn’t about to suggest that a bum wrist kept him from becoming the next Norm Duke.

“I spent two years proving definitively that I do not belong out there with those guys, wrist surgery or no wrist surgery," he said in 2005 to the Capital Times, the newspaper for which he works as a web editor while keeping an active bowling blog called “The 11th Frame.”

Even so, with 29 PBA regional titles to his credit, four USBC Open Championships eagles, and a 1997 Open Championships performance in which he bowled 90 clean frames, you would think that Richgels looks back and wonders what might have been. But then you wouldn’t know Jeff Richgels.

“I don’t know if I would have had a year like Marc did in 1992, but the more success he had the more confident I became that I would have had at least a handful of titles had my wrist cooperated,” Richgels says of watching McDowell win three titles in 1992 including the Firestone Tournament of Champions. “It satisfied that thing in me that wondered how good I could have been had my wrist not hindered me.”

Another thing that Richgels no longer wonders about is whether his spectacular USBC Open Championships record—capped by a Regular All-Events title in 1997—would allow him to join his mentor in the USBC Hall of Fame someday. That day finally came in November, when USBC announced their election of Richgels in the new USBC Performance category created to ensure inclusion of amateur bowlers that excel in USBC championship events.

“I often say that he proceeded to make a liar out of me,” Wonders says these days of his former protégé and, now, his fellow USBC Hall of Famer. “I have had a lot of people ask a lot of questions and learn a lot of things but never be able to apply them. It takes a lot of desire and intestinal fortitude. Jeff put in a lot of work, and his rewards are well-deserved.”

Reprinted from Bowlers Journal International